Image 1 of 5

Image 1 of 5

Image 2 of 5

Image 2 of 5

Image 3 of 5

Image 3 of 5

Image 4 of 5

Image 4 of 5

Image 5 of 5

Image 5 of 5

EHRENBOURG, Ilya. A Street in Moscow

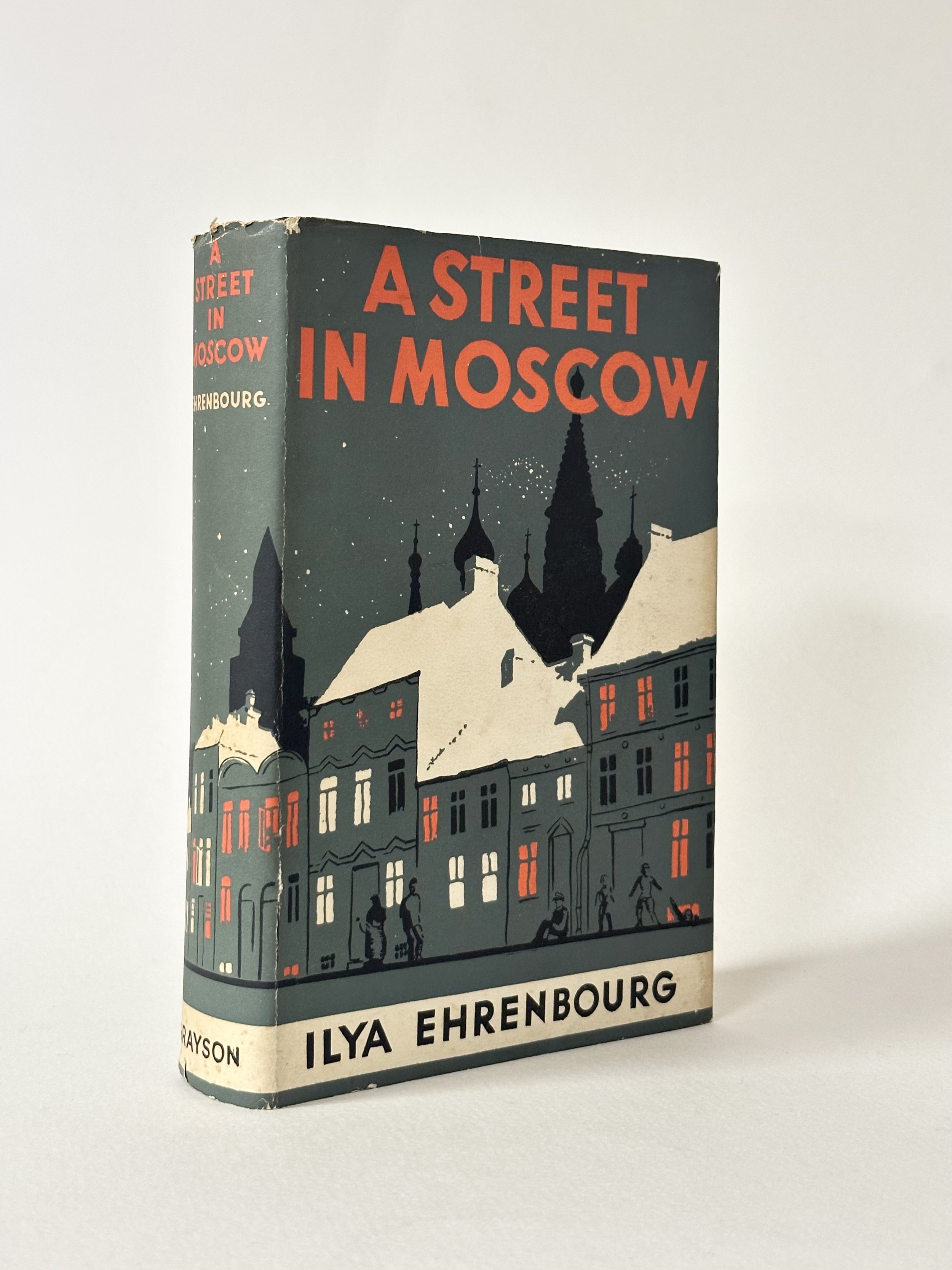

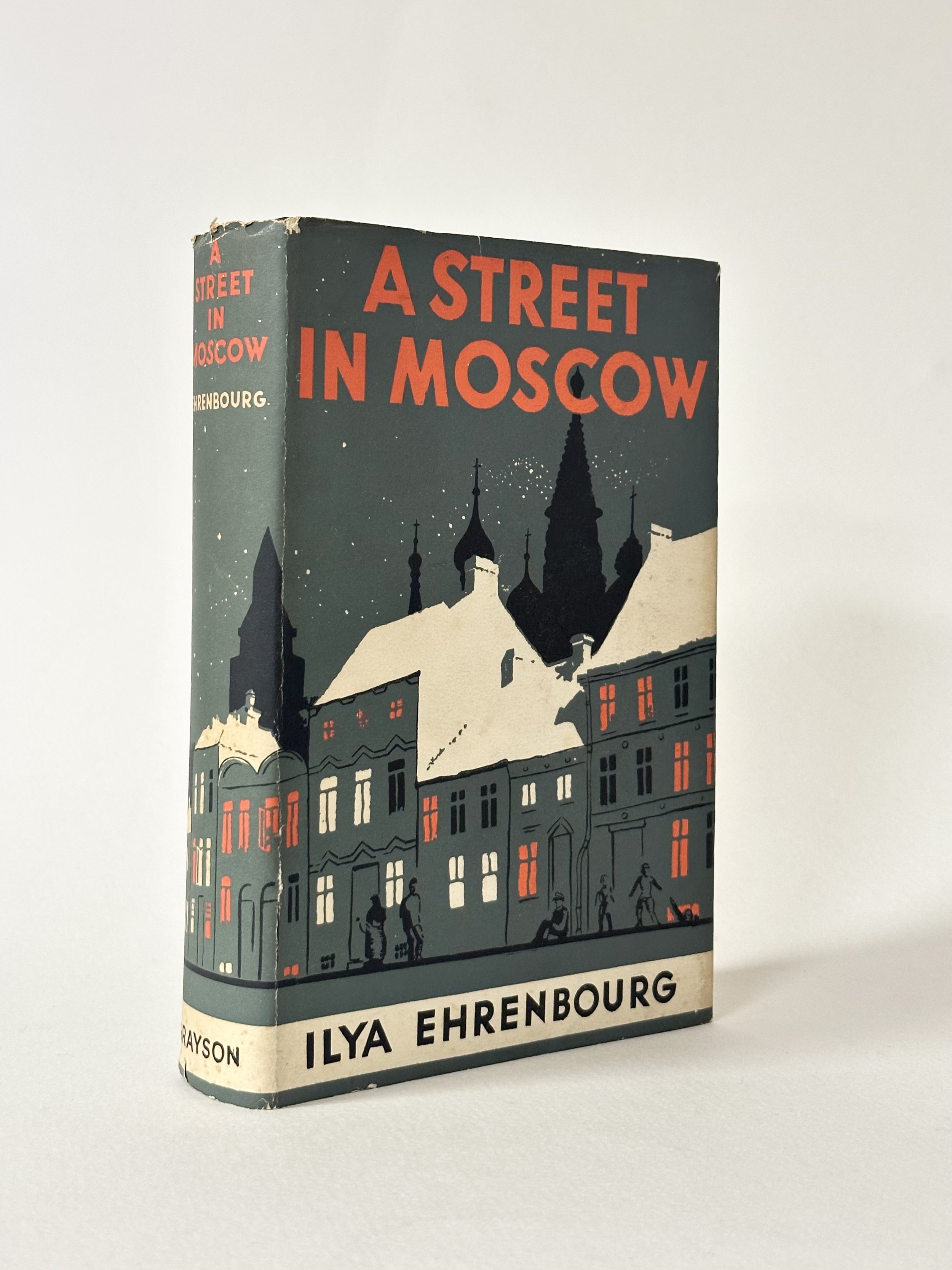

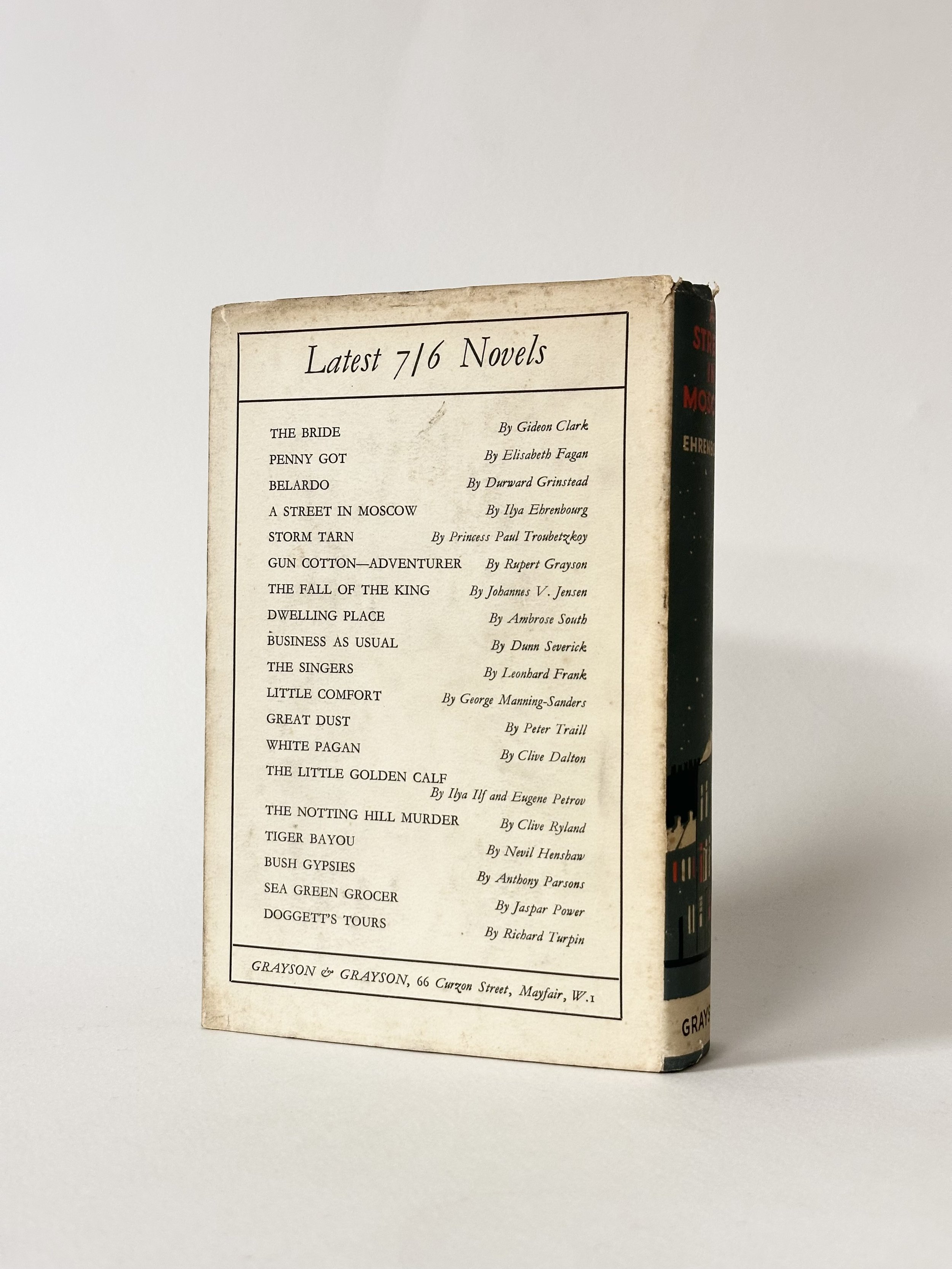

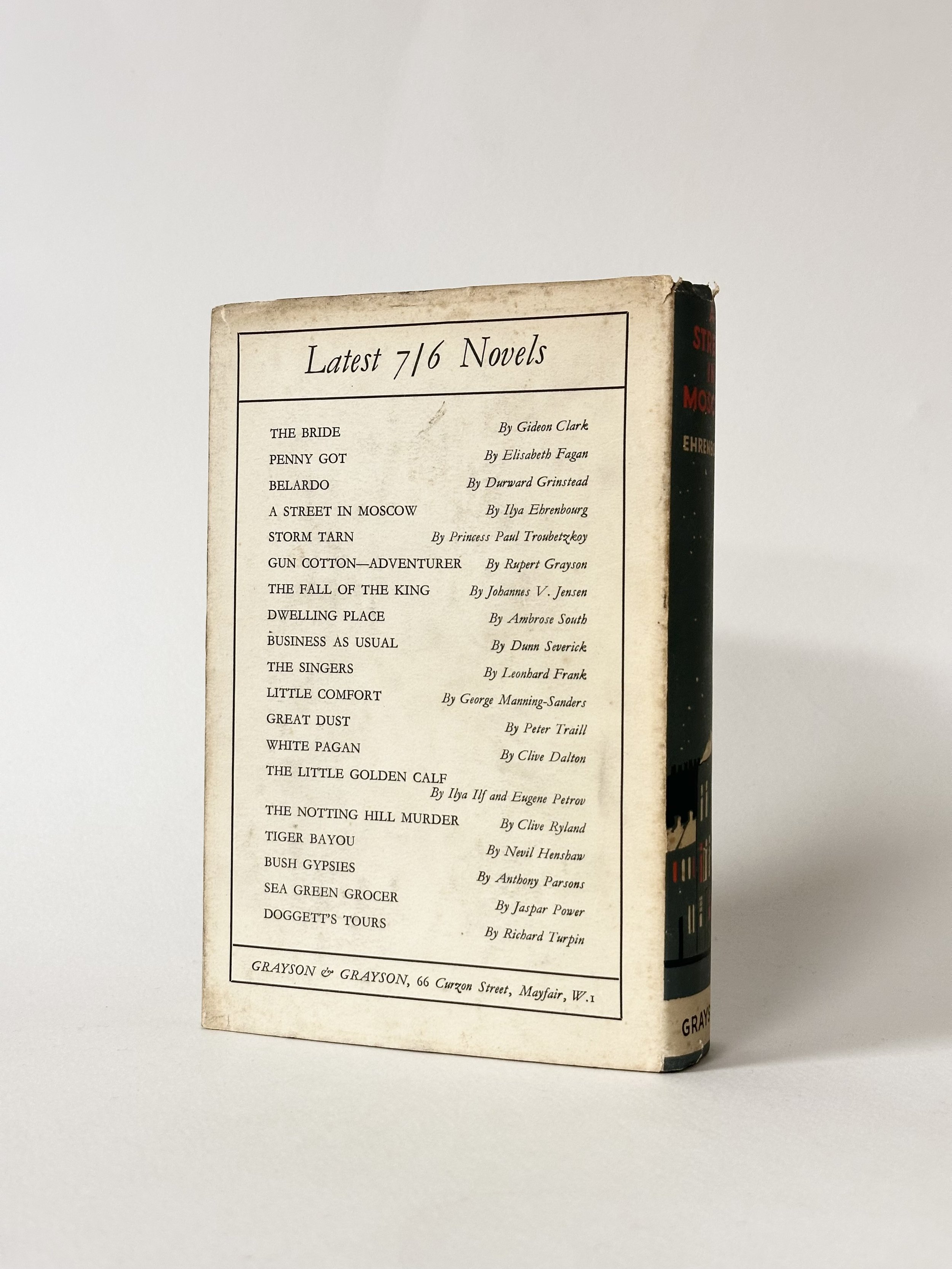

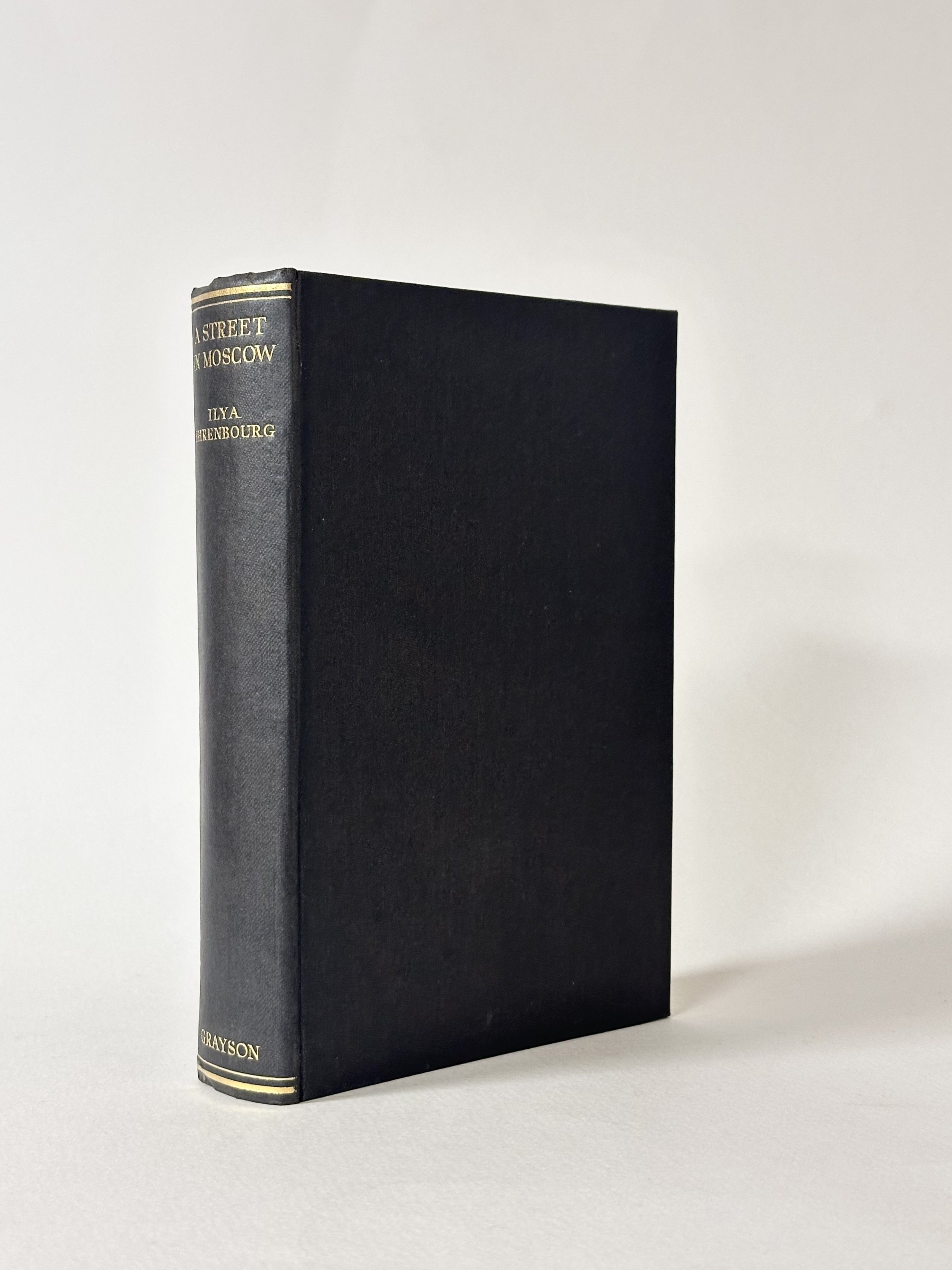

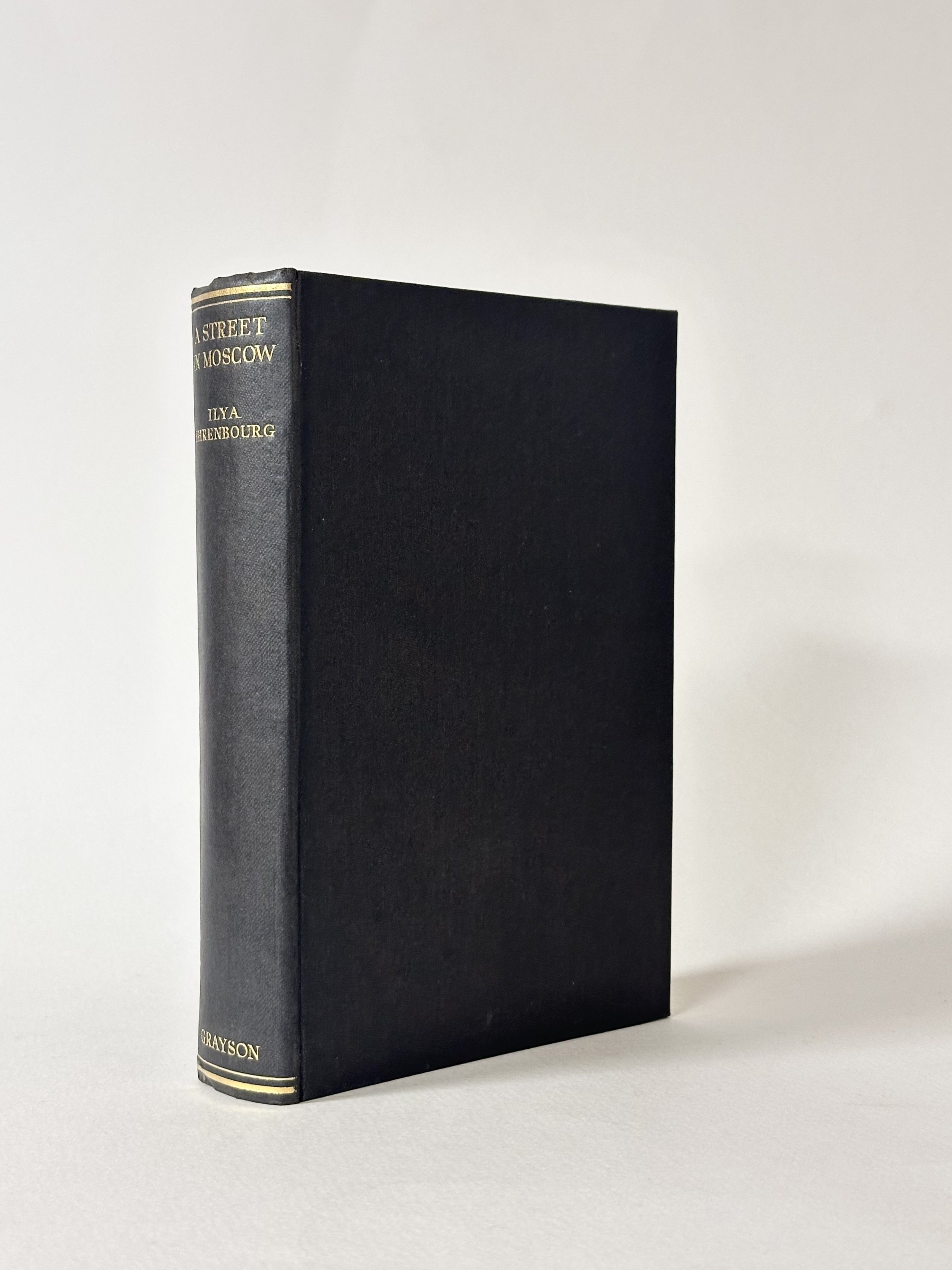

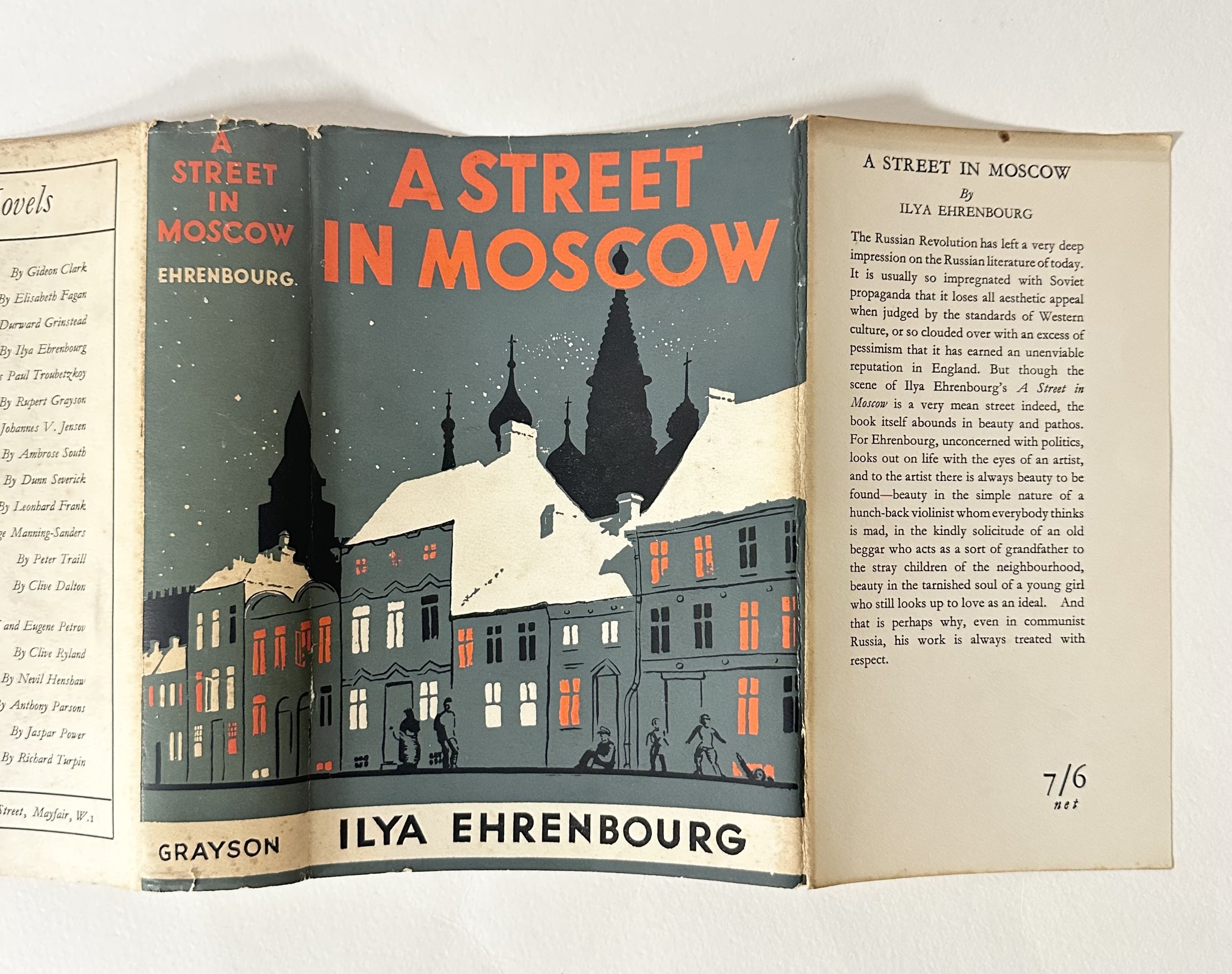

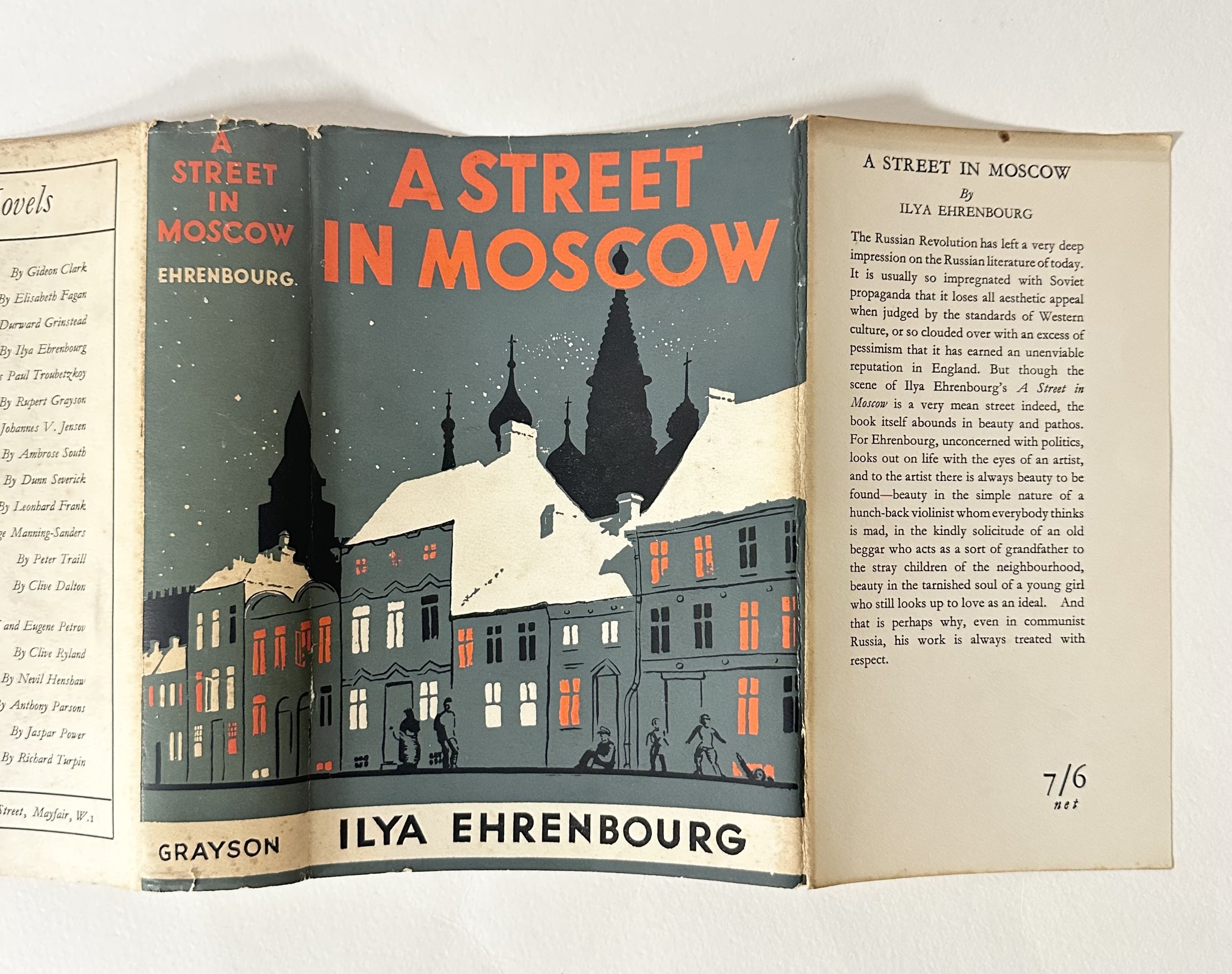

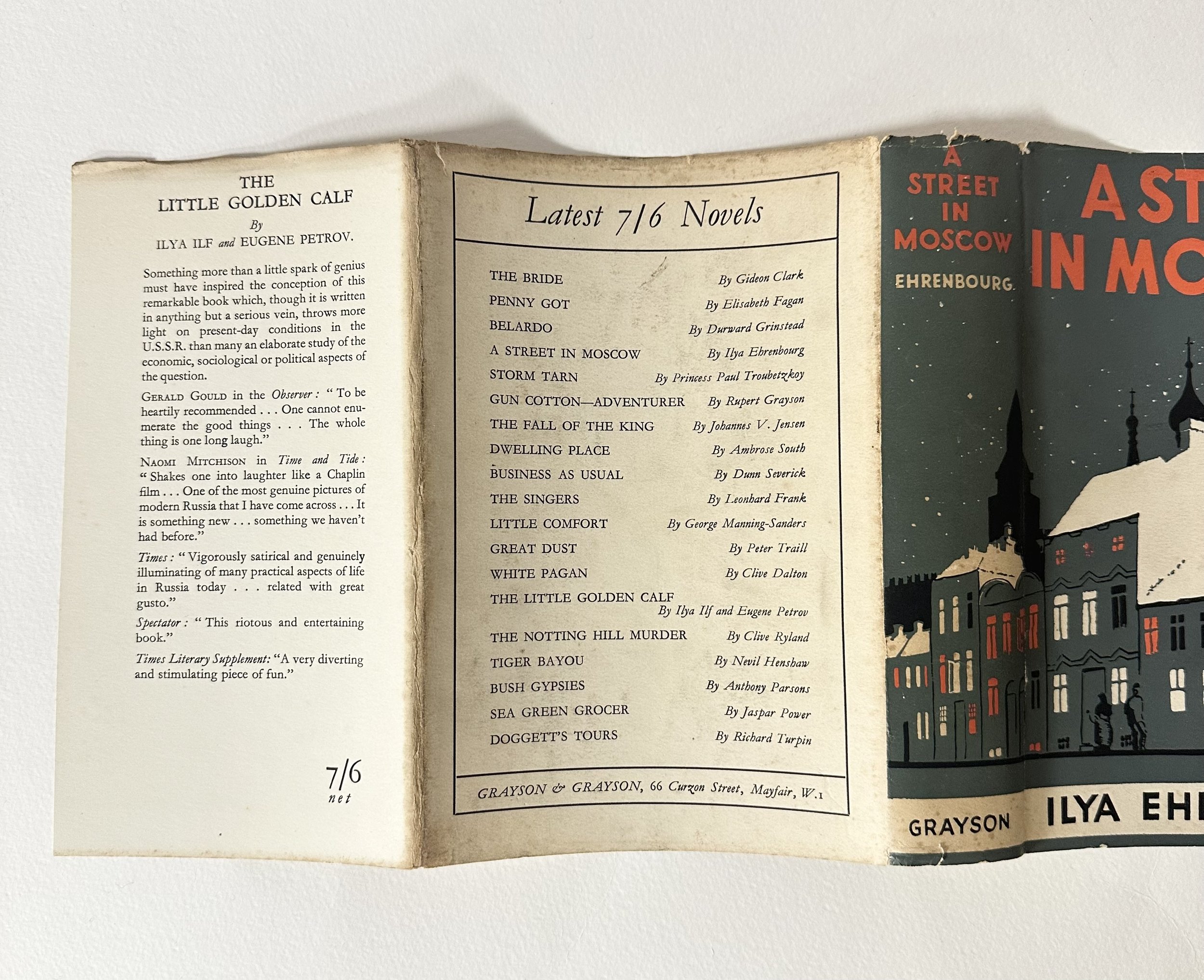

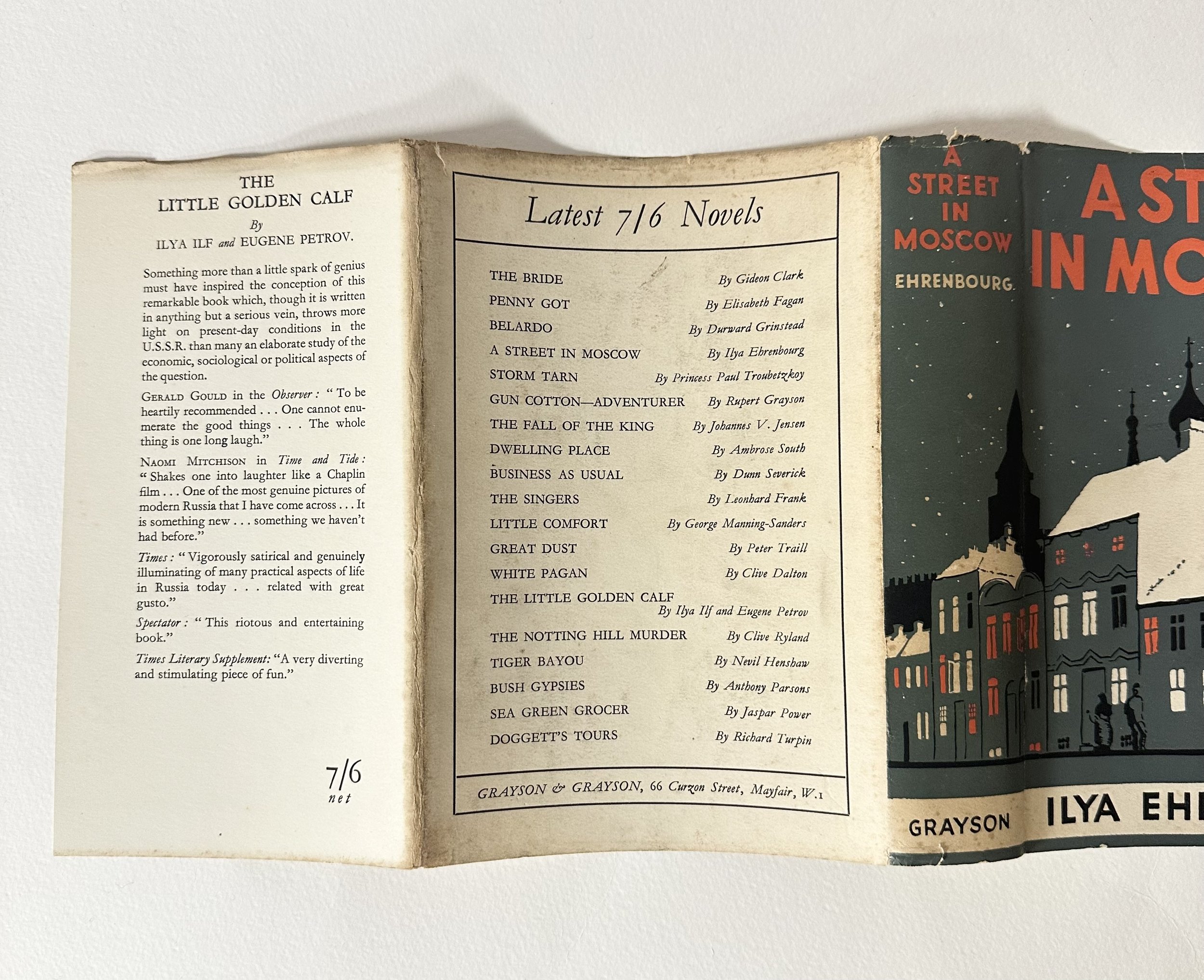

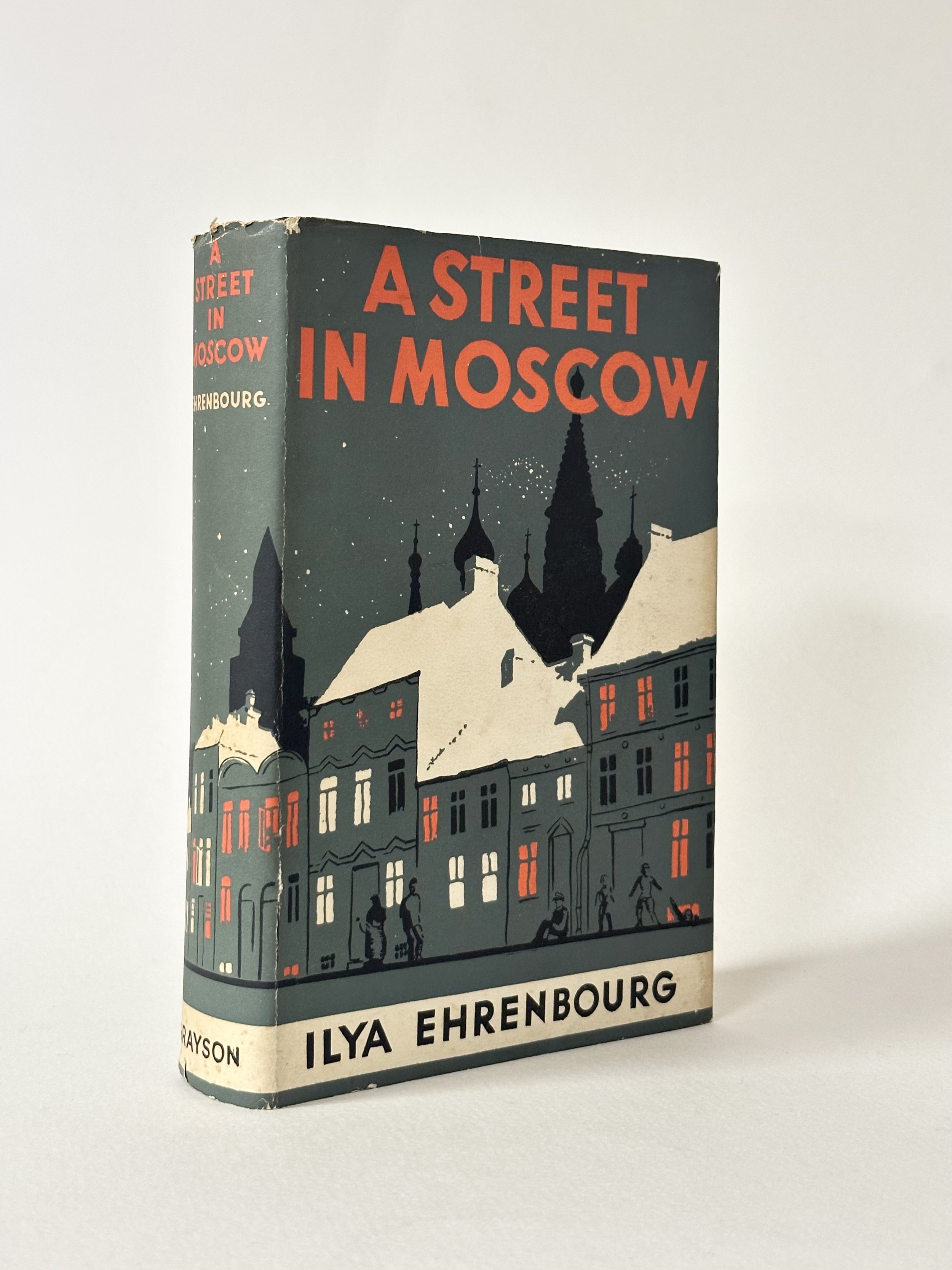

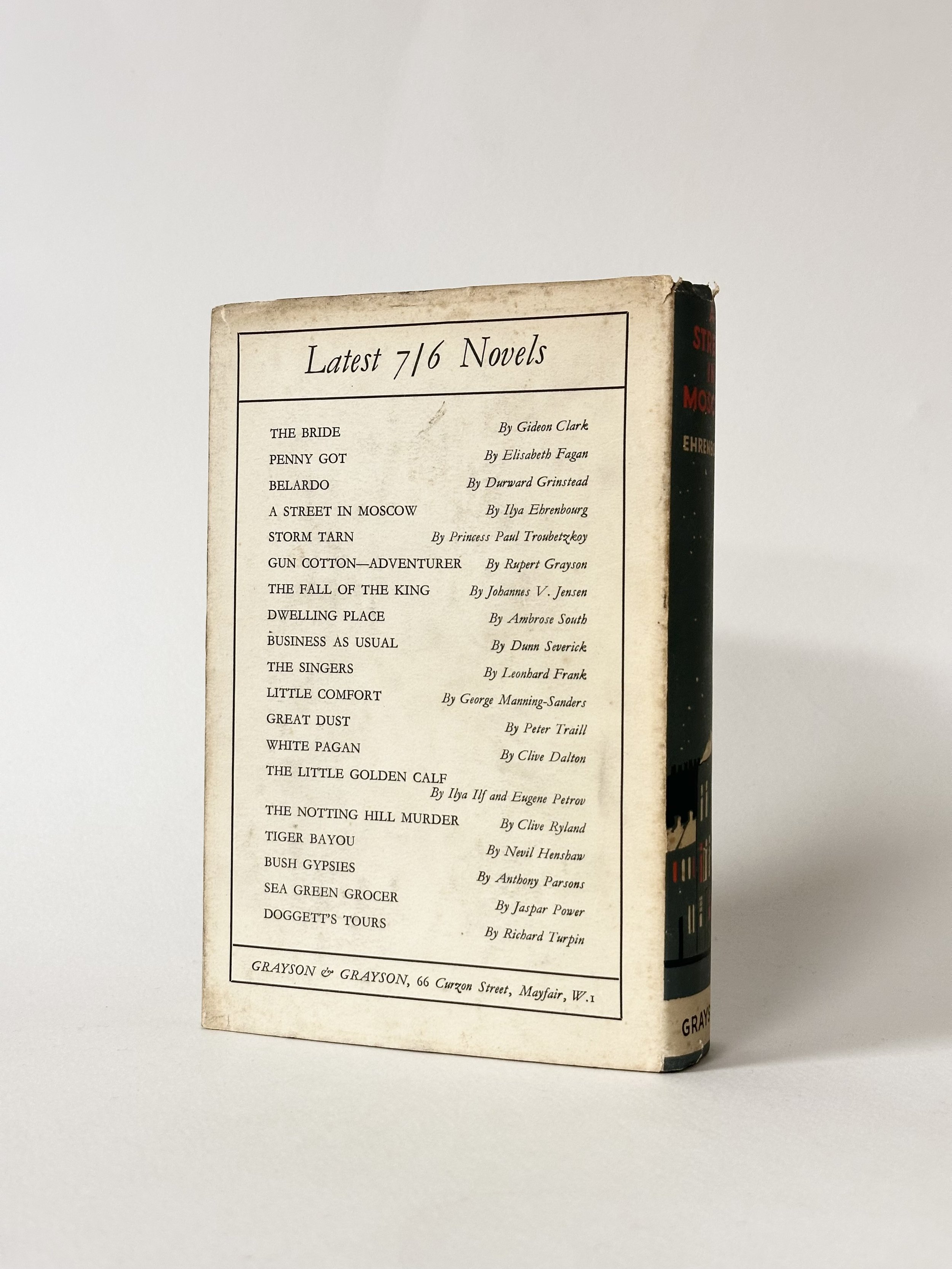

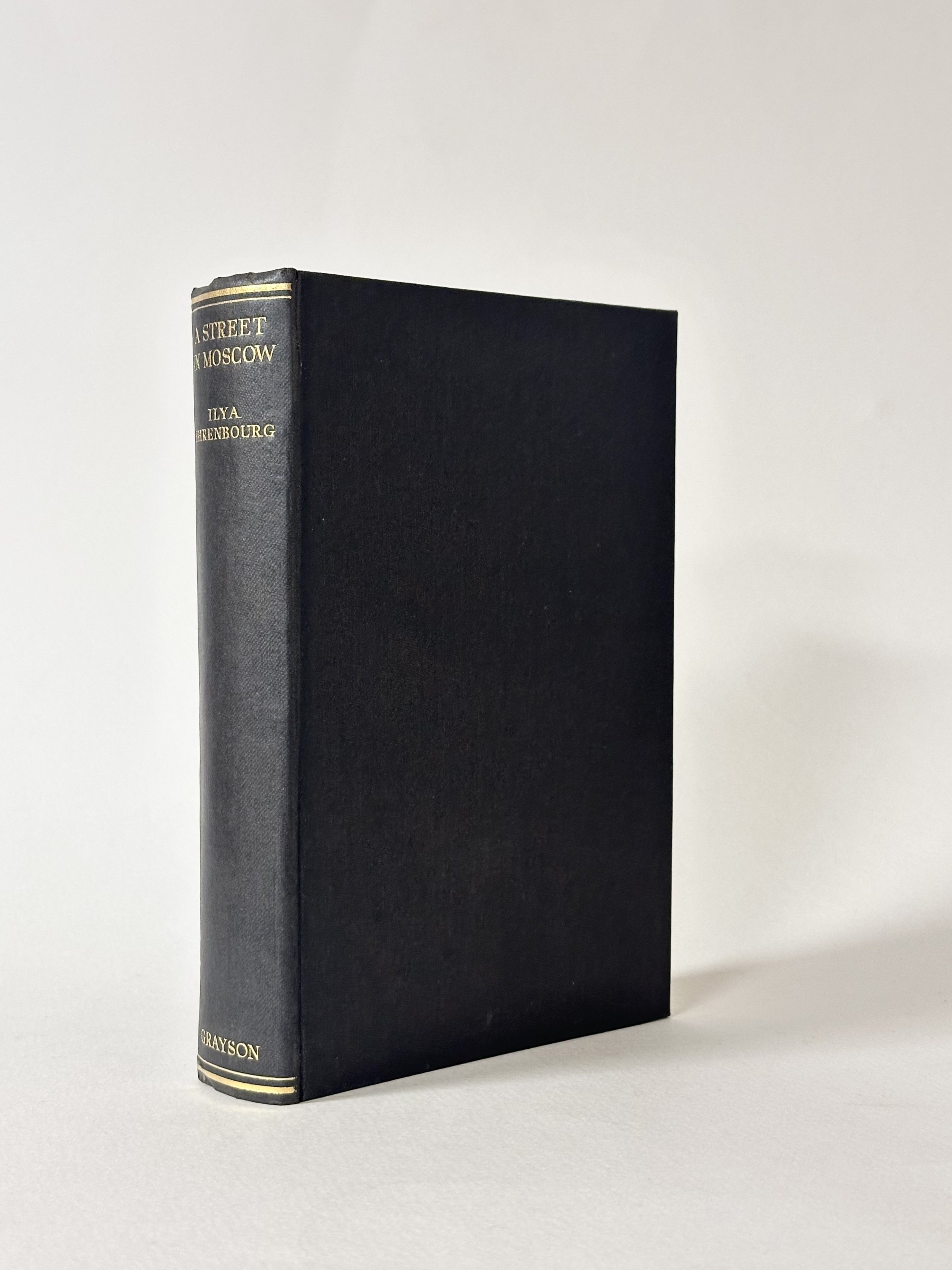

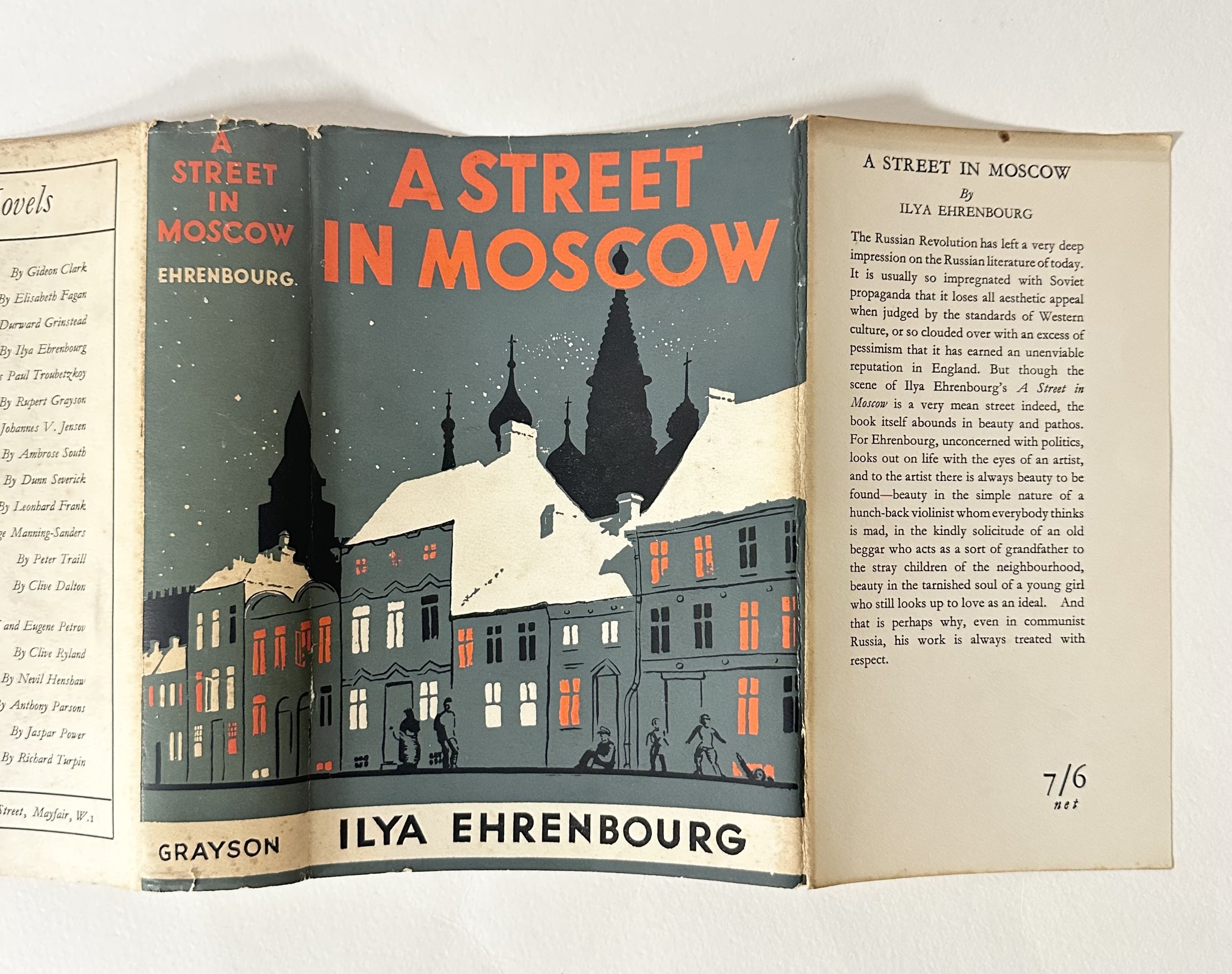

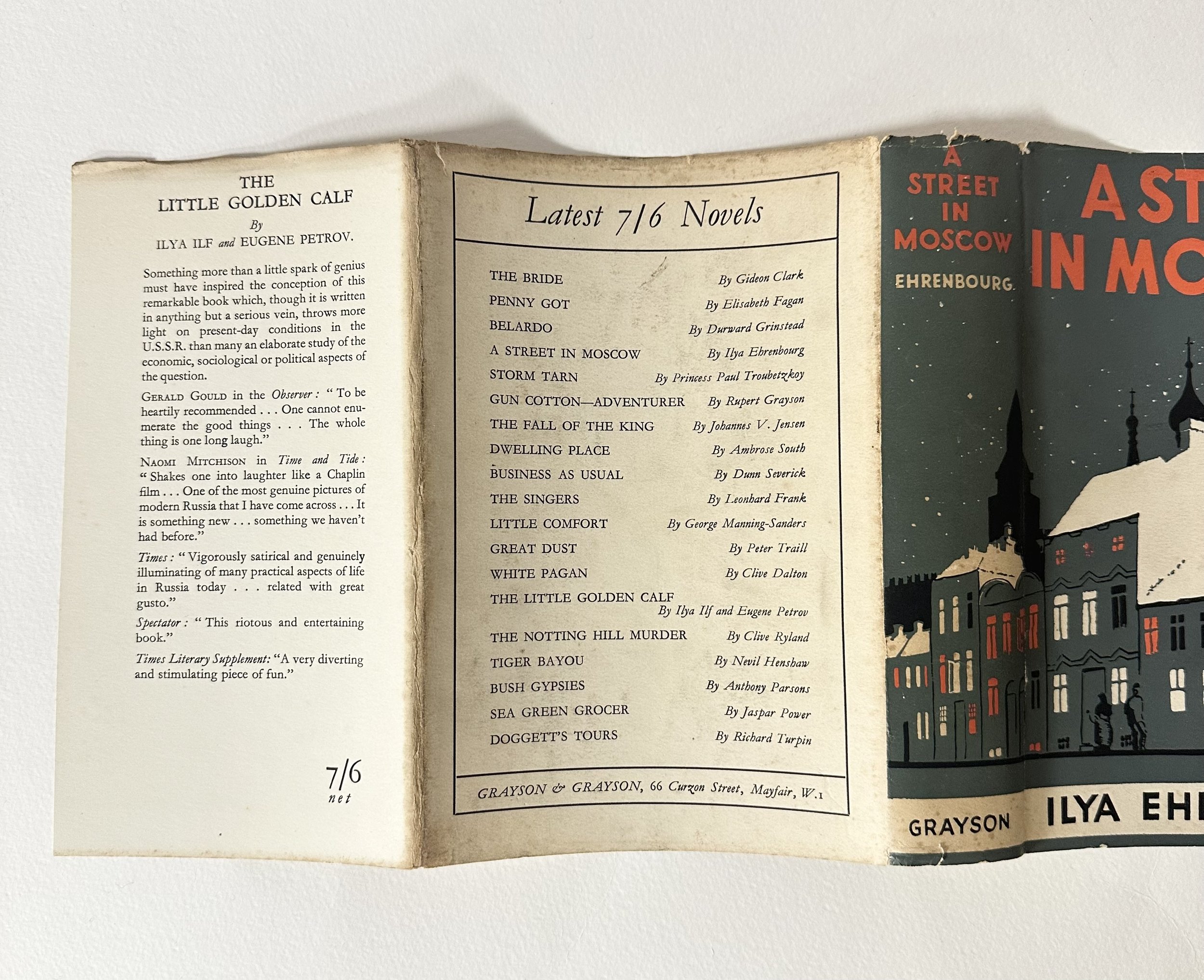

EHRENBOURG, Ilya. A Street in Moscow. Trans. from the Russian by Sonia Volochova. London: Grayson & Nash. 1933. 8vo. First British edition. Publisher’s black cloth lettered in gilt to the spine, in the evocative dust jacket. A terrific example, the cloth just slightly pock-marked in certain light, but clean and sharp, the binding tight and square, the textblock with some faint spots and marks to the textblock. The contents with offsetting to endpapers, very light scattered foxing to prelims, else fine. The dust jacket unclipped (7/6 net) and complete, corners, tips and some joints just gently bumped with a couple of small closed tears, but a sharp copy overall.

An early novel by the talented if not somewhat problematic journalist and novelist who led an unusually colourful life in the Soviet Union, in Berlin, Spain, and in Paris. Ehrenburg was a Soviet journalist who reported on both World Wars and the Spanish Civil War. He was an active revolutionary from a young age, allying with Lenin in the preamble to the Bolshevik Revolution and gaining critical and commercial success pre- and post-First World War, in particular with frontline soldiers for his proletarian sincerity. However, the Bolsheviks rendered him a troublesome writer, since stylistically his characters were considered highly realistic portraits of Russian officials, be they pro- or anti-Bolshevik. Ehrenburg moved to Berlin, then to Paris where he immersed himself in the bohemian scene, settling with many famous artists and writers living there at the time—he became good friends with Pablo Picasso, whose portrait of Ehrenburg is etched into his headstone. He linked up with Ernest Hemingway, Stephen Spender and other Republicans in the fight against Franco, reporting on that war as he did World War One. Though many of his colleagues and associates had perished in Stalin’s Great Purge, Stalin seemed to keep Ehrenburg alive but leashed across Europe. Though he was highly regarded for his fiction—he was industrious, writing over one hundred books—much of it appears entirely inaccessible due to shady censorship. This particular novel follows residents on one mean street of Moscow, written during his hazy days frequenting the Coupole in Montparnasse—the cafe that never closed. Uncommon.

EHRENBOURG, Ilya. A Street in Moscow. Trans. from the Russian by Sonia Volochova. London: Grayson & Nash. 1933. 8vo. First British edition. Publisher’s black cloth lettered in gilt to the spine, in the evocative dust jacket. A terrific example, the cloth just slightly pock-marked in certain light, but clean and sharp, the binding tight and square, the textblock with some faint spots and marks to the textblock. The contents with offsetting to endpapers, very light scattered foxing to prelims, else fine. The dust jacket unclipped (7/6 net) and complete, corners, tips and some joints just gently bumped with a couple of small closed tears, but a sharp copy overall.

An early novel by the talented if not somewhat problematic journalist and novelist who led an unusually colourful life in the Soviet Union, in Berlin, Spain, and in Paris. Ehrenburg was a Soviet journalist who reported on both World Wars and the Spanish Civil War. He was an active revolutionary from a young age, allying with Lenin in the preamble to the Bolshevik Revolution and gaining critical and commercial success pre- and post-First World War, in particular with frontline soldiers for his proletarian sincerity. However, the Bolsheviks rendered him a troublesome writer, since stylistically his characters were considered highly realistic portraits of Russian officials, be they pro- or anti-Bolshevik. Ehrenburg moved to Berlin, then to Paris where he immersed himself in the bohemian scene, settling with many famous artists and writers living there at the time—he became good friends with Pablo Picasso, whose portrait of Ehrenburg is etched into his headstone. He linked up with Ernest Hemingway, Stephen Spender and other Republicans in the fight against Franco, reporting on that war as he did World War One. Though many of his colleagues and associates had perished in Stalin’s Great Purge, Stalin seemed to keep Ehrenburg alive but leashed across Europe. Though he was highly regarded for his fiction—he was industrious, writing over one hundred books—much of it appears entirely inaccessible due to shady censorship. This particular novel follows residents on one mean street of Moscow, written during his hazy days frequenting the Coupole in Montparnasse—the cafe that never closed. Uncommon.

EHRENBOURG, Ilya. A Street in Moscow. Trans. from the Russian by Sonia Volochova. London: Grayson & Nash. 1933. 8vo. First British edition. Publisher’s black cloth lettered in gilt to the spine, in the evocative dust jacket. A terrific example, the cloth just slightly pock-marked in certain light, but clean and sharp, the binding tight and square, the textblock with some faint spots and marks to the textblock. The contents with offsetting to endpapers, very light scattered foxing to prelims, else fine. The dust jacket unclipped (7/6 net) and complete, corners, tips and some joints just gently bumped with a couple of small closed tears, but a sharp copy overall.

An early novel by the talented if not somewhat problematic journalist and novelist who led an unusually colourful life in the Soviet Union, in Berlin, Spain, and in Paris. Ehrenburg was a Soviet journalist who reported on both World Wars and the Spanish Civil War. He was an active revolutionary from a young age, allying with Lenin in the preamble to the Bolshevik Revolution and gaining critical and commercial success pre- and post-First World War, in particular with frontline soldiers for his proletarian sincerity. However, the Bolsheviks rendered him a troublesome writer, since stylistically his characters were considered highly realistic portraits of Russian officials, be they pro- or anti-Bolshevik. Ehrenburg moved to Berlin, then to Paris where he immersed himself in the bohemian scene, settling with many famous artists and writers living there at the time—he became good friends with Pablo Picasso, whose portrait of Ehrenburg is etched into his headstone. He linked up with Ernest Hemingway, Stephen Spender and other Republicans in the fight against Franco, reporting on that war as he did World War One. Though many of his colleagues and associates had perished in Stalin’s Great Purge, Stalin seemed to keep Ehrenburg alive but leashed across Europe. Though he was highly regarded for his fiction—he was industrious, writing over one hundred books—much of it appears entirely inaccessible due to shady censorship. This particular novel follows residents on one mean street of Moscow, written during his hazy days frequenting the Coupole in Montparnasse—the cafe that never closed. Uncommon.